Content marketing is full of ghostwriters, writing under someone else’s byline. But how should a ghostwriting relationship work?

Content marketing is full of ghostwriters, writing under someone else’s byline. But how should a ghostwriting relationship work?

Crikey, marketers and publishers can be slow on the uptake sometimes. Advertising revenue has been declining for decades, leading many to predict the long and painful death of traditional media business models. Add to this the rapid increase of “banner blindness” – as skeptical website visitors filter out display advertising by either ignoring it or using an ad blocker – and publishers have found themselves at war with their own readerships.

Think being a content marketer is tough? Try convincing an entire nation! Anyone fighting to gain or retain the White House needs to know a thing or two about getting a message across in the most persuasive way possible. And with a relentless news cycle in print, television and radio, plus the newer channels of social, email, apps and more, the choice of media can have a massive impact on that message.

Finding a good writer who is also an expert on a niche or highly technical industry topic—and who is also available to write for you at an affordable rate—can be like hunting the proverbial unicorn. Yet the very exclusivity of those skills is what makes the hunt worthwhile.

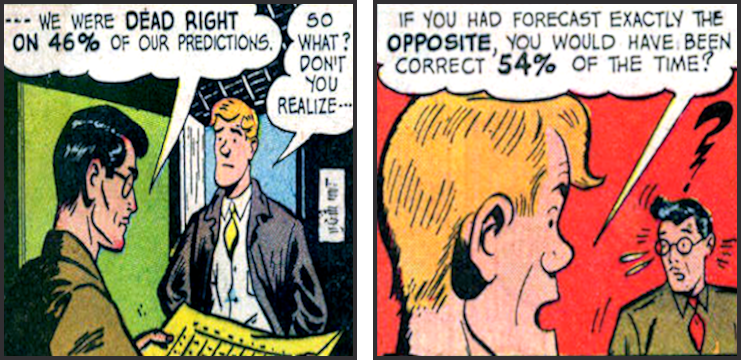

Marketers constantly crunch data to try to determine what works (or doesn’t) and how we can improve or optimise our efforts. Unfortunately, most marketers aren’t data analysts or statisticians. If you want to use maths to answer meaningful questions, you have to know which are the right numbers, how to find them, how to interpret them and which insights to draw.

The internet has forever transformed how we access facts and process information. Yet many marketers still produce content based on the assumption that there is value in merely curating information and facts. Sorry, but if content is to succeed today, it has to be a lot more than just ‘factual’.