Marketers constantly crunch data to try to determine what works (or doesn’t) and how we can improve or optimise our efforts. Unfortunately, most marketers aren’t data analysts or statisticians. If you want to use maths to answer meaningful questions, you have to know which are the right numbers, how to find them, how to interpret them and which insights to draw.

“They’re pretty high mountains,” said Azhural, his voice now edged with doubt.

“Slope go up, slope go down” said M’Bu gnomically.

“That’s true,” said Azhural. “Like, on average, it’s flat all the way.”

Terry Pratchett: Moving Pictures, p141

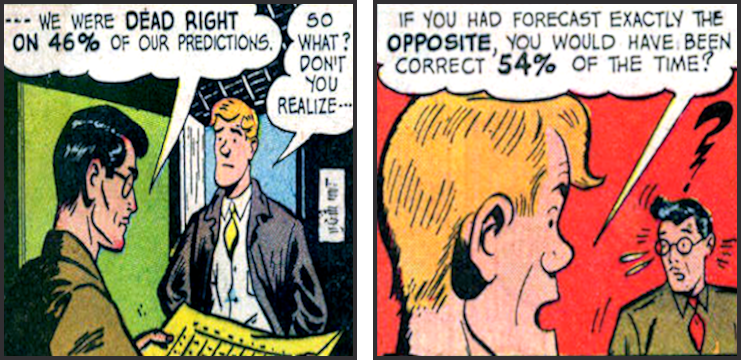

This remains one of my favourite Terry Pratchett gags because I come across variants of this quite regularly in the marketing world. It reflects how statistical information is constantly oversimplified, misinterpreted (or sometimes manipulated) to support an ideal view or draw meaningless conclusions.

This is why I get so frustrated with simplistic claims, such as: “Headlines with odd numbers generate 20% more clicks than headlines with even numbers”.

2020 Update: The post is no longer on the Hubspot website but can still be found via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine: The Anatomy of a Highly Shareable List Post.

That’s not an insight. Saying that most leaves are green doesn’t help anyone understand how chlorophyl works. The article and infographic tell me nothing about why odd-numbered lists may (or, indeed, may not) drive more traffic, which would be far more useful to know. It sticks purely to the numbers as if that’s all the information we need. Follow the formula and the numbers will save you.

Except, they won’t. Statistics need context and interpretation.

Some very odd numbers

I’m pretty certain modern society hasn’t developed an irrational and unexplained bias towards half of all numbers just because they’re odd. There has to be more to it.

When I posted my disbelief on Twitter it prompted an interesting discussion that concluded it isn’t about odds or evens at all. We decided a more likely explanation would be that some numbers seem accurate and authentic while others seem rounded up. 100 Tips to … seems artificial and neat, while 87 Tips to … suggests a more exhaustive, detailed and selective list that has clearly determined there isn’t an 88th tip worth mentioning.

This isn’t a new insight. It’s why Mount Everest was long considered to be 29,002 feet high. In 1856, Andrew Waugh – then British Surveyor General of India – first calculated the height of Everest as exactly 29,000 feet. Convinced that no one would believe his calculations were accurate, Waugh added two feet to the final figure in his report to avoid the impression of having rounded up and thereby protect his reputation. Hence, Waugh became the rather unfair answer to the question; “Who was the first person to put two feet on top of Mount Everest?â€.

Yet Waugh still used an even number to suggest accuracy. While adding three feet may have been too much inaccuracy for Waugh to bear, history fails to record why he didn’t choose to write 29,001 feet instead.

Does a headline promising 88 tips really seem any less exhaustive and specific than one offering 87? I don’t think so – and I doubt any data can definitively show so. And, of course, any odd number that ends in a five can similarly give the appearance of inaccurate rounding, such as 25.

This is why the claim about odd numbers just has to be bogus. This is probably due to someone asking the wrong questions of the available data, and failing to correctly interpret or even validate the results. The original research, and every article that has since repeated the statistic, failed to look beyond the numbers to investigate what may really be going on. Instead, the article and infographic takes the statistic at face value and just moves on to the next simplified, untested claim.

In the case of this infographic, that would be “High quality images get 121% more sharesâ€. But unless you let us in on how “high quality” is defined – and that’s a whole topic of its own – such a statistic is meaningless. You can’t have detailed statistical accuracy at one end of a claim and vaguely defined terms at the other (“engagement”, I’m also looking at you!)

Then there’s “Floating share buttons increase social traffic by 27%â€. Okay, but even Twitter has admitted – and Chartbeat has proven – that there is absolutely no correlation between social shares/social traffic and whether people actually read your content, which must surely be your goal as a content marketer.

Cherry-picking one stat as circumstantial evidence to imply success, while ignoring more relevant and representative data, is real head-in-the-sand stuff.

I could go on, but I won’t. There’s another important issue that becomes obvious once we dig a little deeper into some of these pearls of statistical wisdom.

Is your source a goose, or can I have a gander?

Where do these stats originate? Let’s take my first example about odd-numbered list headlines and trace it back.

While Hubspot highlighted this stat in its social media updates and blog post, the writer’s source was an infographic from Siege Media – an SEO and content marketing agency. The infographic lists some sources at the bottom and it seems this particular stat is taken from an article posted by my mates at the Content Marketing Institute way back in 2011.

Already we can say that this information is five years old, at least. That doesn’t mean the stat is wrong – some trends and behaviours hold true no matter how old. But content styles have changed a lot in the last five years, driven by Google updates, changing social media behaviours and more.

Either way, I’d want to see some more recent data before I repeated the same stat when writing articles and blog posts for clients.

Even the 2011 article isn’t the original source. Written by the Senior Marketing Manager at Outbrain, the post discusses Outbrain’s recent research. “To learn more about what makes readers actually click through, Outbrain […] looked through data on 150,000 article headlines or titles that were recommended across our platform.”

Okay, so we know a little more about the sample size, but still not enough to help us interpret and assess the meagre and sweeping conclusions we’re given. Where are the numbers? What was the methodology? Above all, where is the link to this study?

I spent an hour searching Google for the original source. While I found a number of posts by Outbrain employees on various major websites that referenced the same statistics, and even more blog posts that then referenced those, I was unable to find any original research or any more detailed background to these claims.

This raises a couple of other issues. If Outbrain used unreleased internal research as a PR exercise to get some vague headline-worthy findings into articles on big sites such as Mashable, why does hardly anyone question their conclusions or ask for more evidence? I found only one commenter who asked for a link to the source material (no answer was given).

Alternatively, maybe the Outbrain research was once available but has since been taken down. After all, it was five years ago; web pages come and go. Over the years, the various guest posts may have identified and removed the broken link. If so, I’ve no problem with that. However, if anything, the removal of the link (if there ever was one) is just another indicator to a pedant like me that the information is outdated or no longer relevant.

Either way, both the date and the lack of an original source mean an infographic from December 2015 shouldn’t be repeating questionable stats from 2011. Without an original source, stripped of context and devoid of meaningful insight, it is no more than anecdotal hokum.

Yet marketing blogs and white papers are full of such unworthy claims, given a veneer of authenticity because of our industry’s obsession with data.

Let’s play Numberwang!

Honestly, I’m not picking on Hubspot, Siege Media and Outbrain. The above is just one example of a problem that plagues the entire industry.

Marketing’s obsession with finding a silver bullet formula for success means we are bombarded with advice that is often contradictory, drawing on insufficient data or distorted by generic assumptions.

- Should blog post headlines contain eight or fourteen words?

- Should blog posts be 250 or 2500 words?

- Is it better to send your email newsletter on a Monday or a Tuesday?

Yes, most of the above examples advise caution: There is no definitive answer, there are many other variables in play, don’t take these stats as gospel. In short: “We’re not entirely sure about these findings either.â€

Unfortunately, that doesn’t stop the same stats from being circulated without those caveats and warnings; reduced to basic graphs in infographics, summarised into bite-sized advice in listicles, and truncated into ever fewer characters for social media.

We’re surrounded by outdated findings, poorly sourced statistics and recycled facts that are continually amplified around the echo chamber until they become conventional wisdom.

Ironically, by the time this happens, such wisdom may have very little to do with reality.