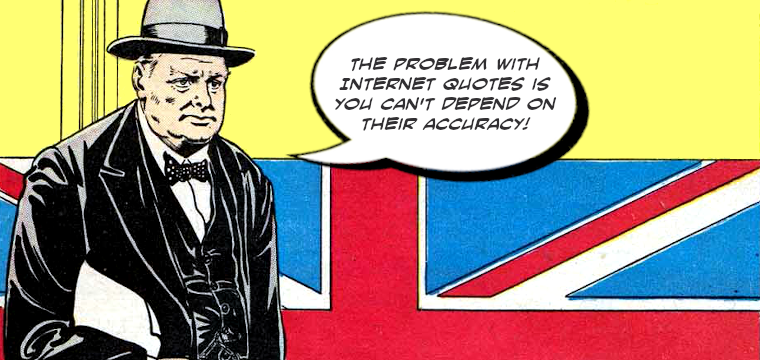

The internet has forever transformed how we access facts and process information. Yet many marketers still produce content based on the assumption that there is value in merely curating information and facts. Sorry, but if content is to succeed today, it has to be a lot more than just ‘factual’.