The internet loves quotations. Social media definitely loves quotations. These days, it seems all you have to do to achieve viral gold is slap an inspirational quote onto a sunset and spam it to every network. But while the right quote, correctly attributed, can lend authority and gravitas to your content, an inaccurate or dodgy quote can just as easily undermine it.

It should come as no surprise that I read a lot. Every morning, I read non-fiction for one hour to try to erode the massive pile of books in my study. In the evenings, I try to fit in another hour of fiction. I’ve also developed the habit of quickly noting down or capturing to Evernote any interesting ideas, facts or quote-worthy lines I might want to use later.

Because I’m a stickler for footnotes and correct referencing, I also note the author, book title, page number, publisher and year. This might seem a bit obsessive and it certainly slows down my reading, but I’ve learned the hard way to capture the good stuff when I find it. I’ve lost too many afternoons trying to remember where I read a particular fact or knockout line to include in an article (and too often failing).

Sadly, I feel I’m in the minority. Sites such as Brainyquote, Quoteland and Wikiquote make it so easy to find quotes on just about any topic. But the sourcing is usually terrible, relying on guesswork, assumption or faulty conventional wisdom. If anything, such websites are part of the problem as – just like the misinformation minefield of Wikipedia – they allow anyone to submit unverified quotations that others then assume have the stamp of accuracy. I can only assume most of these people didn’t have university lecturers hammering into them the need to check their sources, referencing in sufficient detail, for their work to be taken seriously.

Years of researching articles, as well as seeking out and verifying quotations, have revealed to me just how shockingly inaccurate and potentially damaging some can be.

If one of the examples below were to find its way into your content or social media feed, your readers would have good reason to question your fact-checking abilities.

Quotation Mistake 1: The Wrong Words

The level of inaccuracy can sometimes be spectacular, but dodgy quotations aren’t necessarily deliberate. Most probably arise out of sloppy editing, poor comprehension, misplaced trust in an inaccurate source, or even something akin to the game Broken Telephone, where inaccuracy gradually builds upon inaccuracy as the quotation is passed from one person to another. A great example of the latter is discussed in a 2011 article from The Atlantic, which investigates how a Facebook user’s own words ended up being attributed to Martin Luther King – “mangled to meme in less than two days.”

What surprised me about The Atlantic article was the number of people who defended the quote as legitimate, even after learning of the mistake. Apparently, many people don’t understand the point of a quotation.

To them, and possibly many social media users, the message is the thing. We most commonly share quotations because they represent and support our view of the world. Because we agree with the sentiment, it feels “right”. And because it feels right, we’re less likely to question or check its accuracy or authenticity.

However, it doesn’t matter whether the sentiment is worthy or whether the line is representative of the person’s ideas. If the person didn’t say or write it, it isn’t a quote. Period.

Quotation Mistake 2: The Wrong Attribution

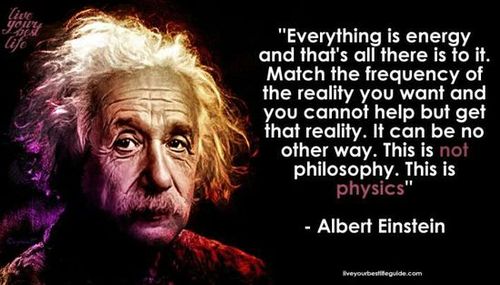

A quotation by a famous figure bestows far greater authority on a message than if we expressed the same idea in our own words. This is why a bad quotation is not always trivial: It lends authority where none may exist; it suggests endorsement where there may be none; and it can even distort or misrepresent the genuine beliefs, ideas and important works of great men and women. Here’s a case in point:

Everything is energy and that’s all there is to it. Match the frequency of the reality you want and you cannot help but get that reality. It can be no other way. This is not philosophy. This is physics.

Albert Einstein (not)

Of course it’s anything but physics. (What does this claptrap even mean, anyway?)

The quotation seems to have originated sometime between 1996 and 2000 – a long time after Einstein’s death then – apparently written by a chap called Darryl Anka on his website promoting his views on trance channelling and his ability to communicate with an extra-terrestrial entity called Bashar. I couldn’t make it up. If you don’t believe me, check out the full story at QuoteInvestigator.com.

Quotations are so often misattributed to Einstein that every time I see or hear a new one, I consider it fake until proven otherwise. For example, I attended a recent event where a speaker attributed Einstein with the following:

If you want your children to be intelligent, read them fairy tales. If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairy tales.

Albert Einstein (?)

It’s a great message, and one I immediately wanted to use when talking about storytelling. But even before the speaker had moved on to the next slide, a quick Google on my smartphone cast doubt upon it.

While there’s no evidence Einstein didn’t say it, the evidence that he did is highly anecdotal, from a single source (since retold many times) and only supports the sentiment, not the specific quote.

Sometimes, however, a quote is more likely to be true than not. It’s just that the proof isn’t a hundred per cent reliable.

One example is the infamous Hemingway line, “The first draft of anything is shit”. I wanted to use this in a recent presentation on content writing; but while it was clearly attributed to Hemingway in a myriad of otherwise-trustworthy journals, books and articles, I could find no mention of when and where he said it.

Quote Investigator again provides more detail, revealing the line first appeared in a posthumous biography of the great writer. Yet, the time between when Hemingway supposedly said it to the biographer (1934) and the publication of the book (1984) – as well as the various hands involved in the manuscript – means there are still question marks about its accuracy.

So, I qualified the quotation by adding the word “apocryphal” in brackets after the attribution: while the quotation is commonly held to be true, it isn’t absolutely certain.

As there is even less evidence to support the Einstein quote on fairy tales, I have so far left it alone.

Quotation Mistake 3: The Wrong Context

Sometimes, a popular quotation can be both accurate and wrong, at the same time! The words might be correct – the attribution might be too – but when separated from the original text and placed in a different context the original meaning can become distorted.

A few weeks ago, I read The Prince by Niccolo Machiavelli (long overdue). In Chapter IX, I came across a familiar line often attributed to Machiavelli.

He who builds on the people, builds on the mud.

Machiavelli, as quoted

Here is the quote at Goodreads, and here it is at AZ Quotes (handily presented as a sharable image for you hip social media cats. See how easy it is for these things to spread?).

The quote regularly pops up in social media and in blog posts; such as this otherwise sterling piece from Lewis University, analysing the Netflix series House of Cards: “Underwood] implicitly agrees with Machiavelli’s idea that ‘He who builds on the people builds on the mud,’ a most undemocratic idea.”

Except – reading the line in context – it wasn’t Machiavelli’s idea, and he certainly didn’t agree with it.

Here’s how the complete passage begins in the most recent Penguin translation of the book:

And if anyone objects to my reasoning here with the trite proverb: the man who builds his house on the people is building on mud, my answer is that …

Machiavelli, The Prince (1532)

It’s a long paragraph, so I won’t repeat the whole thing. However, that opening makes a couple of things immediately clear.

First, Machiavelli calls it a “trite proverb”. Not only did he not coin the phrase, it was already unoriginal and clichéd by the time of his writing.

Second, while he accepts the proverb may be true for private citizens, he goes on to strongly argue that it is absolutely not true for men of power who need the support of the people.

How does the “trite proverb” get attributed to Machiavelli, while his argument debunking it is overlooked and forgotten?

I can only assume the person who first separated the proverb from Machiavelli’s commentary seized on the part that sounded reasonably profound, while doing away with the more complex and nuanced arguments (or failed to understand them).

Quotations are, by their very nature, words taken out of context. The challenge is to quote a line capable of standing alone, so that it doesn’t rely on the surrounding arguments or context to convey its intended meaning. In this case, that definitely didn’t happen.

Don’t Quote Me …

Do I obsess about quotations too much? I don’t think so. Quotations are a useful tool, but only when used carefully and with accuracy.

Whether you’re a blogger, journalist, content marketer, or simply a social media user who likes to share profound nuggets of wisdom, fact checking isn’t optional.

Once you republish the quotation, you become just as responsible for its accuracy as wherever you found it. So it’s always worth taking a little extra time to verify and confirm the accuracy of information and sources you rely on to make your point.

If your audience can’t be sure something as simple as a quotation is accurate, why should they trust the rest of your content?