Just because you’re telling stories on behalf of a brand doesn’t mean the rules are any different than if you were telling fairy tales to young children. There may be more complex ideas and a little less fantasy, but for any story to work, it must still adhere to certain principles. While they might seem arbitrary, these principles are central to how good stories tap into our natural thought processes, sparking imagination, conveying meaning and resonating long after the final line.

Some stories have lasted for centuries in one form or another, constantly being retold to new audiences, who in turn will also pass them on to another generation – usually with a few new twists to keep them fresh. But while many elements of a story can change, in every new adaptation the core elements will always remain the same.

One classic example would be Little Red Riding Hood. This tale can be traced back as part of a storytelling tradition throughout the centuries and across many different cultures around the world. In Africa, the wolf might have been a hyena, in East Asia a tiger. But such things are window dressing. While names, places and other elements change, there is a central strand that can be traced back through the generations like DNA.

In recent years, the story is regularly adapted and reinterpreted for book, film and stage as a comedy, horror, satire and more. My uncle Simon Bor – himself no stranger to adapting fairy stories as the producer of cartoon TV series Wolves, Witches and Giants in the 1990s – recently published his new book Hacked, which tells the same tale of Red Riding Hood entirely as a series of smartphone messages, news reports and apps. The hood is now a hoodie!

This DNA is extremely resilient, and can be summed up with three fundamental questions. If the DNA of your brand story or content is to have the same resilience and power to entertain, influence and be remembered by your audience, it needs to answer these three questions, clearly and unambiguously.

1. Who? The Hero

It is very clear who is the protagonist or hero of Little Red Riding Hood as it’s right there in the title. There may be other characters in the tale, but we only encounter them when they directly help or hinder Red’s journey to her clearly stated goal of getting to grandma’s house. And every hero has a clearly stated goal. Everyone and everything else is irrelevant, except in how they impact on the hero and the goal.

It is very clear who is the protagonist or hero of Little Red Riding Hood as it’s right there in the title. There may be other characters in the tale, but we only encounter them when they directly help or hinder Red’s journey to her clearly stated goal of getting to grandma’s house. And every hero has a clearly stated goal. Everyone and everything else is irrelevant, except in how they impact on the hero and the goal.

Sometimes, the “Who” of your content will be obvious: in a case study, you’re telling the story of a specific customer on their journey to achieve something and how your brand or product helped overcome certain obstacles (impacts).

However, sometimes, your content puts the reader in that role, talking directly to them about a particular stage on their journey towards a particular goal, with advice, actions and relatable scenarios. While a step-by-step tutorial may not be a story in the classic sense of “once upon a time” to “happy ever after”, each step can still be analogous to a scene. And to give each scene a relatable context, you need to write the content with a specific customer persona in mind.

For example, a wide range of writers, marketers and curious visitors arrive on my website every day. Yet this particular post is written specifically to appeal to the content marketer eager to improve the quality of their branded storytelling. Sure, it means this post may be less relevant to non-marketers, but writing to appeal to everyone only ever results in generic, less insightful and less relatable content.

In short: focus your content by considering the narrative of a specific customer persona.

Note: the story is never really about your brand or product, even when it is. Paradoxical, I know. Each is merely a character – ideally the trusted mentor and not the bumbling villain – or prop in someone else’s tale.

In all cases, you want the reader to recognise him or herself in the content, either by proxy (“This case study describes someone just like me”) or more directly (“This tutorial has helped me take action in my own quest”).

2. What? The Central Message

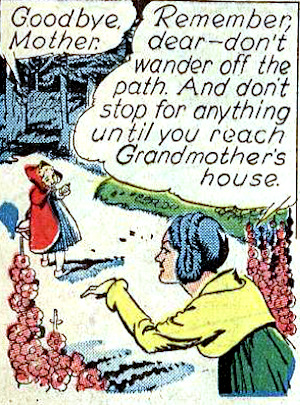

The central lesson of Little Red Riding Hood is a warning. “Don’t be tempted from the safe path, or wolves might get you.”

The central lesson of Little Red Riding Hood is a warning. “Don’t be tempted from the safe path, or wolves might get you.”

For centuries, children were told variations of this tale when there was a real threat from wolves and other nasties hiding in nearby forests. But as children would often lack personal experience of these dangers (if they did it was probably already too late) they would have little understanding of the consequences of disobeying their parents’ warnings. Adults just want to stop kids having fun, right? The safe path is booooooring.

So tales like Little Red Riding Hood helped children to imagine the consequences of deviating from safety. On hearing these stories, they would hopefully develop a greater respect for sticking to the rules and heeding the advice of parents.

Kids today have less reason to be concerned by wolves; never mind witches and giants. So to keep the central message clear, modern adaptations often reinterpret the wolf either metaphorically or literally as a more human predator. Stranger danger. Either way, the central message remains the same. Heed the warnings. Stick to the safe path. Trust your parents.

Your message needs to be equally clear and simple to express. Your content may include oodles of information and complex advice, but you should never leave it up to the reader to interpret its significance. Each piece of content should lead to one clear conclusion. If you want the reader to take away one thing above all else from the story, it is a central message that should resonate and motivate, inspire and inform.

When planning your content, always have this clear message or conclusion in mind. Then, when reviewing your content, try to cut away anything unrelated or that detracts from this central point – even if you think it is interesting or entertaining. You don’t want the audience to become distracted or reach a different conclusion. Your key message allows you to refine and improve your content with much greater focus and precision. This clarity of message is what people will remember.

3. Why? The stakes

Why should we care about what happens in your story? In Red’s case, because people can die as a consequence! Before the Victorians decided to give the story a happy ending with a convenient woodsman, the original tale saw Red’s misadventure lead to the bloody death of both her grandmother and herself. The stakes very clear: Wayward children cannot rely on luck and a passing woodsman to save them.

Why should we care about what happens in your story? In Red’s case, because people can die as a consequence! Before the Victorians decided to give the story a happy ending with a convenient woodsman, the original tale saw Red’s misadventure lead to the bloody death of both her grandmother and herself. The stakes very clear: Wayward children cannot rely on luck and a passing woodsman to save them.

Marketing is all about trying to convince people that our products or services can meet a particular need (the central message), backed up by the consequences of not doing so (the stakes). Not every story is a life or death proposition, but the bigger the stakes, the more persuasive and motivating the message. The more trivial a story feels, the less likely we are to see it through to the end. So choose your stories wisely.

Happily Ever After …

Who, what and why: three simple questions that your story cannot survive without.

When preparing your content, spend a little time jotting down your answers to these three questions, or add them to your briefing template when commissioning writers. Not only will these three questions help you structure and produce your content much quicker by focusing your thoughts, they will also ensure each piece of content is clearly aligned with your strategic goals.