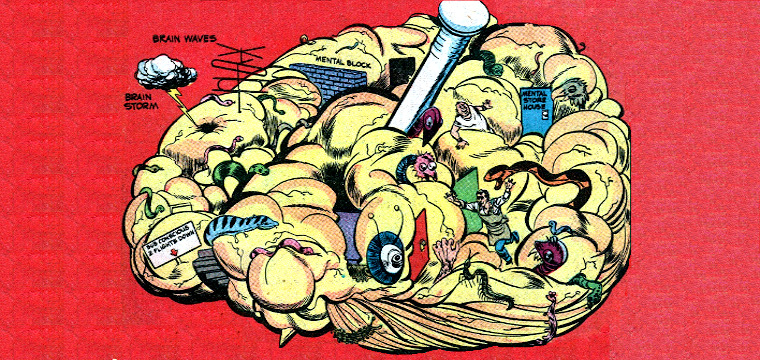

Content marketers often rely on numbers to convey information and motivate consumers: web pages devoted to lengthy tables of technical specifications; white papers packed with charts and graphs; blog articles that reduce complex topics to lists of statistics. And there’s no doubt that such data-rich content can work—to a point. However, numbers aren’t nearly as persuasive, nor as easily understood, as we would like to believe.